Imagine your city with a 50 percent reduction in obesity, a 60 percent reduction in commute times, a 90 percent reduction in carbon emissions, and greatly enhanced innovation and opportunities for entrepreneurs. Sound too good to be true? Think again. “Smart Cities” save time, reduce pollution, provide economic advantages and improve overall quality of life.

It is time to transform cities, built with 19th and 20th century infrastructures and technologies, into efficient, safe and fulfilling Smart Cities of the 21st century. Transforming a city into a Smart City requires a systemic “whole-city” approach with six essential ingredients, pulled together by appropriate mixed-use density. The ingredients are: (1) Smart Mobility, (2) Smart Living, (3) Smart Government, (4) Smart People, (5) Smart Economy, and (6) Smart Environment.”1  Smart Mobility provides mixed-modal access allowing residents to travel efficiently by car, foot, bike, or public transport. Smart Living means a city is safe, healthy, culturally vibrant and happy. Smart Government and Smart People foster an inclusive society with transparency and open data, embracing creativity and providing 21st century education. Smart Economy promotes entrepreneurship, innovation, productivity and local to global interconnectedness. Smart Environment ensures the other five ingredients are achieved in a sustainable manner using green buildings, green energy and green urban planning.1 Barcelona is an example of one exceptionally Smart City, not only because it utilizes all six ingredients well, but, most importantly, because of its density.

Smart Mobility provides mixed-modal access allowing residents to travel efficiently by car, foot, bike, or public transport. Smart Living means a city is safe, healthy, culturally vibrant and happy. Smart Government and Smart People foster an inclusive society with transparency and open data, embracing creativity and providing 21st century education. Smart Economy promotes entrepreneurship, innovation, productivity and local to global interconnectedness. Smart Environment ensures the other five ingredients are achieved in a sustainable manner using green buildings, green energy and green urban planning.1 Barcelona is an example of one exceptionally Smart City, not only because it utilizes all six ingredients well, but, most importantly, because of its density.

In the race to stand out, cities worldwide have branded themselves as “Smart Cities,” when in fact most possess only one of the six ingredients necessary to allow their citizens to experience the full benefits and advantages of a 21st century Smart City. As a result, “Smart City” has become an overly used, ill-defined term. One common definition mentioned by the American Planning Association (APA) defines Smart City as a city where “communication technology is used to engage citizens, to deliver city services and to enhance urban systems resulting in cost efficiencies, resilient infrastructure and an improved urban experience.”2 Under this definition, any city in which residents use the Uber app qualifies as “Smart.” Technology may increase a city’s “IQ,” but density and mixed-use development are what make a city inherently smart.

Even the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) aims too low. In its Smart City Challenge, a program to help define what it means to be a Smart City, USDOT has pledged up to $40 million to the “country’s first city to fully integrate innovative technologies – self driving cars, connected vehicles, and smart sensors into their transportation network.”3 Although these technologies are a step toward addressing our outdated infrastructure and increasing commuter safety and cost efficiencies, this one-dimensional approach will not foster the promise of revolutionary change and improvement to the quality of life a truly Smart City offers. Federal, state and local governments are struggling to maintain overextended roads, power lines and other infrastructure that serve our nation’s cities. The idea that technology alone (like embedding smart sensors into roads) will address this array of complex issues is shortsighted and will significantly increase the capital and maintenance costs of infrastructure.

The money dangled by USDOT’s Smart City Challenge focuses on only one of the six Smart City ingredients, Smart Mobility. Even there its effort falls short because it seeks to further our dependency on automobiles. It does not seek to add transportation options. This means it falls short of truly achieving a Smart City. It is like saying you own a computer, when all you really own is the keyboard. Investing in a narrow area of Smart Mobility is the start of a creating a Smart City, but without expanding transportation options and without the other five ingredients, it is incomplete.

Creating a city with all six Smart City ingredients may appear unrealistic and unachievable, but several cities have successfully done it. Barcelona is one of those cities.

When thinking of Barcelona, what comes to mind are beaches, sunny weather and modernist architecture. As the annual host of the Smart City Expo World Congress, however, Barcelona is gaining a reputation as an innovative, Smart City. How has this 2000 year-old city successfully implemented all six ingredients?

To best answer this question, think about making a pizza. Without an oven, we just have raw dough, sauce and cheese. The oven is the essential mechanism that pulls these ingredients together. Similarly, without a mechanism, there can be no Smart City; just a mixture of ingredients acting independently of one another. The mechanism to pull the Smart City ingredients together is mixed-use density. It is the key to Barcelona’s success.

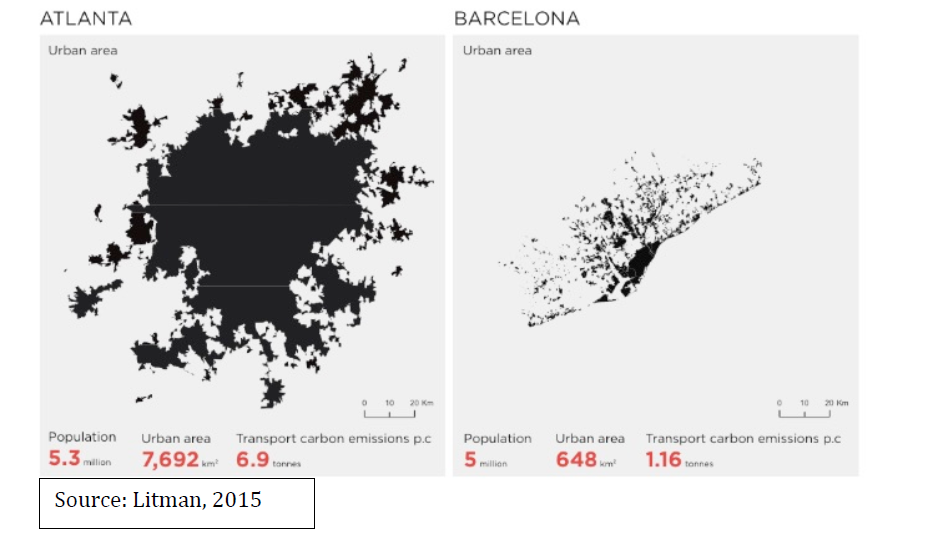

Barcelona, with an average population density of 15,926 inhabitants per square kilometer, is one of the densest cities in Europe. 4 Most development is mixed-use with residents living above businesses, schools and government buildings. Comparing Barcelona with Atlanta, Georgia shows why density and mixed-use are so important to a city’s IQ.

Barcelona and Atlanta are surprisingly similar — both have urban populations of about six million people.5 Both are economic powerhouses in their regions and both hosted Olympic games.6 Their density however is drastically different. Barcelona is one of the densest cities in Europe and Atlanta is a sprawling city.

In Atlanta, the average resident’s daily commute is over an hour. 1 Residents in outlying counties spend even more time behind the wheel, averaging 72 minutes per day.8 Almost 300 hours, or more than seven weeks, is lost per person per year sitting in traffic.7 This costs Atlanta’s local economy over $3.73 billion per year in lost productivity.7 In Barcelona, only 21 percent of the population commutes to work by car.9 Forty-four percent of commuters walk or bike and 35 percent use public transportation.9

The average commute time on Barcelona’s heavily used bike sharing program is only 13 minutes each way.10 The average Atlanta commuter spends 62 percent more time, an additional month per year, commuting to work than the Barcelona biking commuter. Density benefits the city’s residents in other ways. First, Barcelona residents emit a fourth of the carbon emitted by residents of Atlanta as illustrated in the chart below.

Second, the residents of Barcelona experience substantial health benefits from its Smart City approach, not enjoyed by Atlanta residents. At 26.8 percent,11 Atlanta’s obesity rate is well above Barcelona’s 16 percent obesity rate.12 Studies show that for every additional five minutes Atlanta-area residents drive each day, they are 3 percent more likely to be obese.13 There is a clear correlation between mode choice and obesity.

Second, the residents of Barcelona experience substantial health benefits from its Smart City approach, not enjoyed by Atlanta residents. At 26.8 percent,11 Atlanta’s obesity rate is well above Barcelona’s 16 percent obesity rate.12 Studies show that for every additional five minutes Atlanta-area residents drive each day, they are 3 percent more likely to be obese.13 There is a clear correlation between mode choice and obesity.

Finally, Barcelona’s density has allowed it to create and implement a meaningful public transportation network, a transportation option unavailable to the vast majority of commuters in Atlanta. Barcelona is 28 times denser than Atlanta.6 This means Atlanta requires a transport network 28 times greater than Barcelona’s to move the same number of people. The metro network in Barcelona is 99 kilometers (60 miles) long with 60 percent of the population living less than 600 meters from a metro station.6 Atlanta’s metro network is 74 kilometers (45 miles) long but only four percent of the population lives within 800 meters of a metro station.6 If Atlanta sought to provide its population with the same metro accessibility that exists in Barcelona, (i.e., 60 percent of the population within 600 meters from a metro station) Atlanta’s Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority system would need to add an additional 3,400 kilometers (2000 miles) of metro tracks and about 2,800 new metro stations to transport the same number of people that Barcelona does with only 99 kilometers of tracks and 136 stations.6

This simple comparison shows how Barcelona has pulled four Smart City ingredients together through its density. Its density has reduced its dependency on the motor vehicle, which has allowed most people in Barcelona to walk, bike or take transit (Smart Mobility). These transportation choices significantly reduce Barcelona’s output of carbon (Smart Environment), and allow people to live a more active, healthy lifestyle resulting in lower obesity rates (Smart Living). Transportation options provided by density mean it’s efficient to get from point A to point B, saving billions of dollars in saved time (Smart Economy). Just like the oven that brings all ingredients together to bake a pizza, mixed-use density brings ingredients together to create a Smart City.

When it comes to Smart Government and Smart People, it is fair to say that Atlanta and Barcelona are fortunate to have both. Density however, fosters a riper environment for Smart People and Smart Government to collaborate. Collaboration leads to new technological innovation, which is why Barcelona is now a hotbed for tech startups. Don’t believe me? Look at San Francisco, New York City or Boston; the three most walkable and dense cities in the U.S., and also three cities with some of the highest rates of patents per capita.14 When most U.S. patent applications list similar patents that influenced them, they point to other innovators located less than twenty-five miles away because of face-to-face collaboration.13 Collaboration is easier and more convenient in Barcelona than in Atlanta simply because of the significantly less distance to travel to meet within the city.

Barcelona is implementing many of the inventions provided by its growing number of tech startups. For example, the city has installed routers on most street corners, providing free wifi citywide. High density allows fewer routers to achieve coverage, reducing capital and maintenance costs of the network. Free wifi is a valuable service for the large number of walking commuters navigating the city, and provides access to innovative apps like Barcelona Contactless, which provides information on nearby facilities, services, events and activities. 15

Barcelona’s bike sharing program, Bicing is one of the most successful bike sharing programs in the world. The service covers over 70 percent of the city with over 6,000 bicycles, each used 10 to 15 times per day. The demand is so high that tourists cannot participate in the program because there are not enough bikes.10

Citywide wifi, Smart City apps and Bicing are just a few of the growing number of Barcelona Smart City innovations. These undeniably improve the quality of life for the average Barcelona resident, but they are not the reason Barcelona is smart. Barcelona’s mixed-use, high density is what makes these innovations meaningful. Because of high density, Barcelona is inherently smart; these inventions just make it smarter. This rule applies everywhere. Technology alone cannot make a Smart City. Mixed-use density is the key. Technology just makes a city smarter.

Sprawl costs the U.S. $1 trillion per year because of infrastructure capital and maintenance expenses, congestion, accidents, obesity, and pollution.5 If USDOT is serious about creating a Smart City with all 6 ingredients, it should invest in a city that already has them, like San Francisco, Boston or New York. As for other cities that want to become Smart, rather than attempting to compensate for their inherent deficiencies with technology, they should focus, first, on creating policies to limit sprawl, such as preventing developers from continuing to build single-family subdivisions on undeveloped land. Next they should start changing zoning laws to stimulate live-able downtowns with mixed-use high density and in-fill development. Only policies like these have the potential of fostering cities that are truly “Smart.”

As Jane Jacobs put it:

“You can’t rely on bringing people downtown, you have to put them there.” -Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Author Bio:  Kevin Rayes is a transportation planner and is passionate about creating high quality cities that serve all citizens in a sustainable fashion, a.k.a. “Smart Cities.” https://www.linkedin.com/in/kevinrayes

Kevin Rayes is a transportation planner and is passionate about creating high quality cities that serve all citizens in a sustainable fashion, a.k.a. “Smart Cities.” https://www.linkedin.com/in/kevinrayes

1. Cohen, Boyd. “6 Key Components for Smart Cities.” UBM’s Future Cities. 19 Dec. 2012. Web. 1 May 2016. <http://www.ubmfuturecities.com/author.asp?section_id=219&doc_id=524053>.

2. “Smart Cities and Sustainability Initiative.” American Planning Association Apr. 2015: 6-7. Print.

3. “Smart City Challenge Notice of Funding Opportunity.” U.S. Department of Transportation. Web. 7 Mar. 2016.

4. “Ajuntament De Barcelona.” Generalitat De Catalunya. Web. 20 Mar. 2016.<http://municat.gencat.cat/index.php?page=consulta&mostraEns=0801930008>.

5. Litman, Todd. “Analysis of Public Policies That Unintentionally Encourage and Subsidize Urban Sprawl.” Victoria Transport Policy Institute (2015). Web. 12 May 2016. <http://static.newclimateeconomy.report/wpcontent/ uploads/2015/03/public-policies-encourage-sprawl-nce-report.pdf>.

6. Richardson, Harry W., and Chang-Hee Christine Bae. Urban Sprawl in Western Europe and the United States. Burlington: Ashgate, 2004. Print.

7. “Traffic Becomes a Factor for Atlanta Businesses.” AJC.com. 7 May 2015. Web. 12 May 2016.

8. Goldberg, David, Jim Chapman, Lawrence Frank, Sarah Kavage, and Barbara Mccann. “Linking Land Use, Transportation, Air Quality and Health in the Atlanta Region.” University of British Columbia. Web. 17 May 2016.

9. Sun, George, Evan Gwee, Lim Chin, and Augstine Low. “Journeys.” Land Transport Authority 12 (2014). Web. 12 May 2016.

10. “Información Del Sistema.” Bicing.cat. Web. 12 May 2016. <https://www.bicing.cat/es/informacion/informacion-del-sistema>.

11. “Obesity Rates for States, Metro Areas.” Governing. Web. 12 May 2016.

12. Olabarria, Marta, Katherine Pérez, and Elena Santamariña- Rubio. “Daily Mobility Patterns of an Urban Population and Their Relationship to Overweight and Obesity.” Transport Policy 32 (2014): 165-71. Web. 25 May 2016.

13. Speck, Jeff. Walkable City: How Downtown Can save America, One Step at a Time. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012. Print.

14. “Patenting and Innovation in Metropolitan America.” Brookings Institution. 1 Feb. 2013. Web. 12 May 2016.

15. “Àrees Smart City.” Smartcity.bcn.cat. Web. 12 May 2016 16. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Print.

[…] que les rodea. Como resultado, los niveles de contaminación han disminuido, al igual que las tasas de obesidad. Y, por supuesto, los residentes se sienten comprometidos con la ciudad en que […]